An ElastiCache Migration Story

The Problem

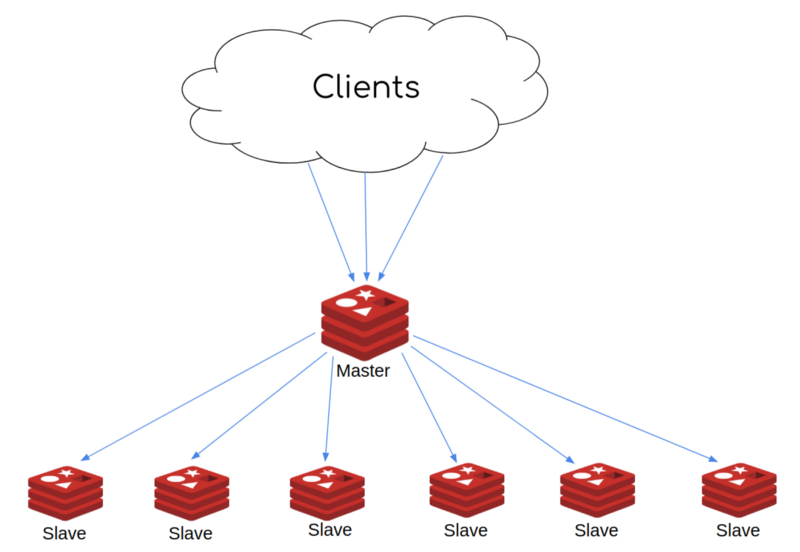

At Beat, a tech company that has been around for a while, our product consists of a bigger, constantly decreasing in size, monolith and a constantly increasing number of microservices. For our services that need persistence, we use several kinds of databases to store their state and, at the same time, we have chosen Redis to be leveraged as a second-layer cache in front of them. So far we have been using the AWS ElastiCache managed service in a disabled cluster mode. While this architecture served us quite well for some time, it recently caused us some headaches and it soon became obvious that we could no longer scale any further with this setup.

From the above graph, it’s easy to identify that the master node is a bottleneck and the only way to scale up is vertically. We tried to do this a couple of times but it was painful and a cause for downtimes. Furthermore, scaling vertically was increasing our AWS bills by a fair amount without allowing us to use the full potential of these instances. Even adding a single node to the cluster was very time consuming and sometimes was causing periods of small or even big downtimes.

Adding to all the above, our monolith service is prone to creating hotkeys that can cause spikes of load on specific events. We knew this was not ideal and was on our radar to refactor it but this would take some time. In the meantime we wanted to have a system that could scale much better.

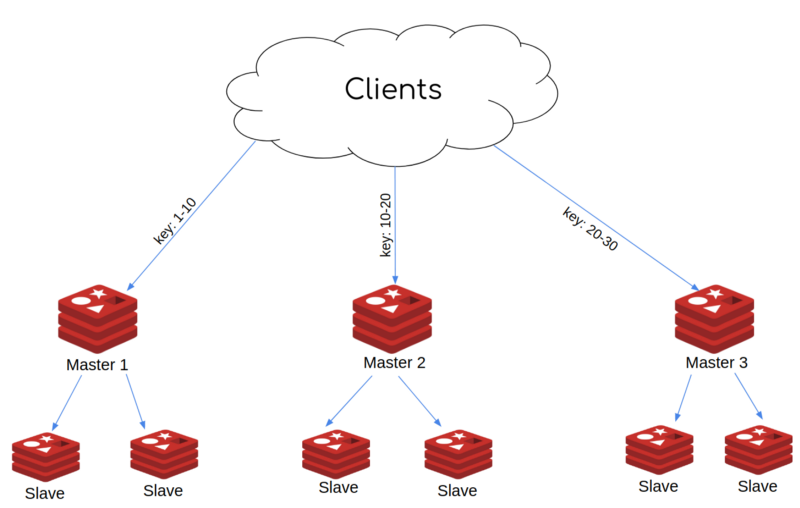

In order to tackle the problem and prevent bigger downtimes in the near future, we decided to assemble a subteam consisting of backend, QA, and infrastructure engineers that would be on this full-time in order to come up with an alternative scalable solution. After several internal whiteboard sessions, some reassuring talks with our AWS technical account manager and support engineers, and of course generous portions of coffee, we decided to go with a cluster mode enabled architecture. In theory, this would allow us to scale and load balance traffic from our heavy-loaded masters. The new architecture would look like:

Stress testing the new solution

Before investing multiple people’s time and energy on the new architecture, we wanted to see if it would meet our expectations and cover our needs for growth. Our main specifications were the following:

- If a specific shard node is overloaded, we should be able to add replica node(s) without any impact to the existing cluster.

- If a specific shard is getting significantly more load than others, we should be able to create a new shard and rebalance our cluster without any downtime or impact to our clients.

- If we want to scale a cluster vertically and change our instance types, it should be without downtime.

For each of these tests we created a test cluster that we loaded with some dummy data and we started making queries from multiple clients.

We used tools like memtier and redis-benchmark, as well as some home grown scripts that allowed us to make our testbed as close to our production as possible and also allowed us to test our use cases.

When our tests showed us that we had the green light to use this architecture, we moved to the next phase which was capacity planning for the new cluster.

Capacity Planning

After the stress tests showed us that the new setup was promising and had all the needed checkmarks, we went through our current system and calculated the resources we needed to serve the current load at the time. The goal was for the initial version of the new setup to be able to withhold double that load. After that, any scaling should be easy to happen.

The fact that Redis server is single threaded allowed us to focus on metrics like memory, network bandwidth, and number of connections for the whole cluster.

We aimed to plan our capacity on the conservative side for a couple of reasons. We could add more shards and replica nodes later easily without any downtime and we also knew that, from the client’s point of view, we had some improvements in the pipeline that would help reduce our cluster load.

Migration Time

Once we were ready for our new cluster and the codebase to support it, we came up with a release plan that consisted of multiple phases. We wanted each phase to introduce as few changes as it could at the same time within our system. This way, it would be easier to observe the impact of each change in a far easier and clear manner.

Phase 1 (or the “Testing the waters” phase)

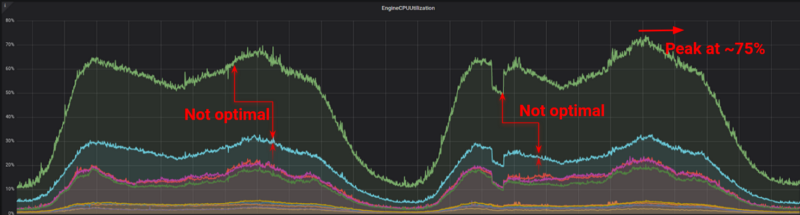

For the first phase, we didn’t make any radical changes on our backend besides the fact that we should support Redis cluster mode, and we enabled the cluster on a smaller portion of our users, initially in the Greek market. After our quality assurance engineers gave us the green light, we made the switch. The results, however, were not very impressive.

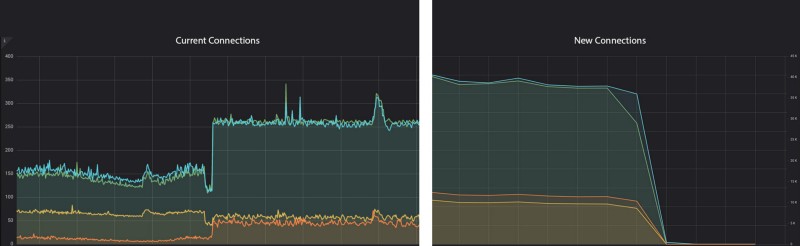

The graphs above showed us that our new cluster was somehow load balancing our traffic in a better way and the load was split between the multiple masters. However, the traffic distribution was not as expected, so we continued digging in and making our traffic better distributed across our nodes.

Phase 2 (or the “We’ve just getting warmed up” phase)

We did have, however, a hidden ace up our sleeve; we were suspecting that our new clients were not using persistent connections. Using the tcpconnect script from bcc tools, we observed a huge rate of new connections towards the Redis cluster’s TCP port.

astrikos@co-247-api-100:~$ sudo /usr/share/bcc/tools/tcpconnect -P 6379

PID COMM IP SADDR DADDR DPORT

28083 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.3.61 6379

23983 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.3.251 6379

17563 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.2.214 6379

21281 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.2.248 6379

757 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.2.214 6379

13566 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.2.138 6379

4982 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.2.27 6379

1084 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.3.120 6379

21281 php-fpm7.1 4 10.9.0.92 10.9.3.219 6379

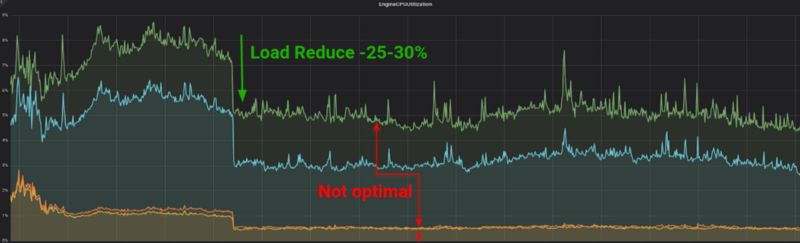

With every Redis command, we were creating a new connection to the server. That, of course, was very expensive for the ElastiCache nodes on system level, since it was causing the Linux kernel to work a lot on opening and closing these new connections. After we deployed our code with the new persistent connection flag, we were delighted to see the following impact.

As you can observe, CPU went drastically down, current connections increased, since now they were long lived, and new connections decreased to almost 0. Also rerunning the tcpconnect tool showed us a dramatically decreased rate of new connections within our instances.

Phase 3 (or the “Finding needles in a haystack” phase)

We still, however, hadn’t solved our problem of specific shard masters not being balanced loaded. We knew that our Redis traffic pattern was a ratio of 1:7 write/read commands, which meant that the master nodes shouldn’t be that loaded if traffic were split between master and replicas. It was time for some network inspection to see what kind of traffic we exchange with the different Redis cluster nodes. After firing a tcpdump in one of our instances that was running clients to our cluster, we noticed something that was interesting:

20:54:36.071016 IP 10.3.2.202.52244 > 10.3.2.246.6379: Flags [P.], seq 119034:119078, ack 77591, win 852, options [nop,nop,TS val 9057048 ecr 2717873315], length 25: RESP “GET” “core\_settings”

20:54:36.081016 IP 10.3.2.246.6379 > 10.3.2.202.52244: Flags [P.], seq 119000:119034, ack 119078, win 227, options [nop,nop,TS val 3670031817 ecr 10018445], length 29: RESP “MOVED 13782 10.3.2.35:6379”

Our client instance is the machine with IP 10.3.2.202 and the Redis replica node is the IP 10.3.2.246.

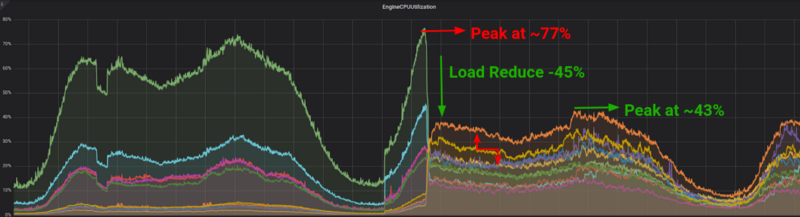

We knew from the cluster sharding map that the specific Redis replica was part of the shard that was responsible for the key we asked for. The response we got, though was a MOVED response that was redirecting us to another instance with IP 10.3.2.35 that happened to be our master node for this shard. After some research, we discovered that in order for our replicas to respond to READONLY commands, we would have to prepend a READONLY prefix in front of our commands. Our backend engineers prepared the changes in our codebase and as soon as we deployed the new changes, we saw the following:

That had done the trick, the gap between the master and the replica nodes had significantly closed down.

Phase 4 (or the “Finishing touches” phase)

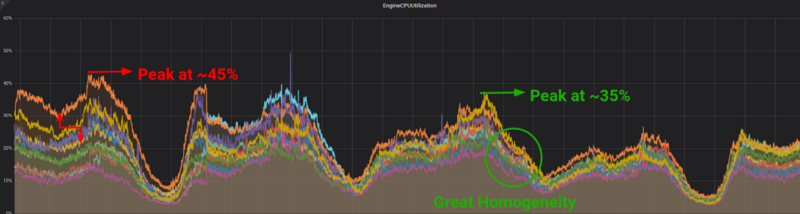

Something in the graphs, however, still didn’t allow us to justify that cold beer that comes after a good win. If you look carefully at the above graph, our master nodes were no longer getting as much traffic as we would have expected. What seemed to have happened, was that we moved our traffic from our masters to our replicas, resulting in a non-homogeneous traffic pattern. Talking with our backend engineers, this proved to be a feature of our internal library, which was developed as part of our previous setup. Since we didn’t need it anymore we disabled it and allowed master nodes to get a piece of the read only queries as well. After this final touch, we had the following satisfying results.

Phase 5 (or the “Celebrate” Phase)

It was finally time to celebrate and enjoy that cold beer we had been dreaming of for the last couple of weeks. The graph below was finally what we were expecting and hoping for.

Conclusion

All Beat Engineers are proud of working together as one team. We managed to make this happen in just over two weeks because multiple teams and engineers from different domains, expertises and crafts, joined forces and worked in harmony. From our infrastructure engineers preparing the clusters, to the backend engineers hacking in our codebase and libraries, and our quality engineers making sure everything worked as expected before we went live each time, everyone worked together and, above all, had fun.

This post was originally published in Beat Engineering Blog, as part of my engineering work at Beat. Cross-posting here for posterity reasons.

An ElastiCache Migration Story

It also lead to an AWS case study that can be read in here.